Organic architecture embodies a design philosophy that emphasizes the seamless integration of human dwellings with the surrounding natural environment.

This approach aims to create buildings that feel symbiotically integrated with their sites, as if the structures had grown naturally from the surrounding landscape.

Key Takeaways

- Organic architecture blends buildings with nature, emphasizing harmony.

- Utilizes natural materials, forms, and light to connect with environment.

- Aims for sustainability, enhancing well-being and reducing energy use.

I find this form of architecture inspiring for a more sustainable future, and this is why in this blog post, I’ll explore what organic architecture is, its key principles, famous examples, benefits, and how this approach can help create a more sustainable built environment.

Origins of Organic Nature-Inspired Architecture

The term “organic architecture” was initially coined by the celebrated American architect Frank Lloyd Wright during the early 20th century. Wright’s vision for organic architecture was to create structures that authentically represented their specific era and location.

Rather than imitating past architectural styles or imposing a rigid external geometry, Wright sought an architecture that harmonizes and blends with its natural surroundings. He believed buildings should feel innate to their sites, enhancing the existing landscape rather than competing with or dominating it.

At its core, this architectural style aims to create buildings that feel unified with nature. Structures are designed to integrate with their sites and feel sympathetic to the existing environmental context. It’s an approach that rejects imposing artificial forms in favor of architecture that feels native to a place.

Key Principles

Frank Lloyd Wright outlined several guiding principles for organic architecture:

- Integration with site – The building grows naturally from its site and landscape.

- Use of natural materials – Natural materials like wood, brick, and stone are prioritized.

- Natural light and ventilation – Windows and spaces maximize the use of natural light and airflow.

- Space flows – Spaces connect and flow into one another.

- Natural shapes and forms – Forms echo shapes seen in nature.

- Human scale – The size and proportions relate to and make sense for the human body.

By following these principles, the goal is to create architecture that feels innately connected to both people and nature. Buildings strive to exist in harmony with their sites.

Famous Examples

Some of history’s most celebrated buildings demonstrate core principles of this architectural design style. Here are a few popular examples:

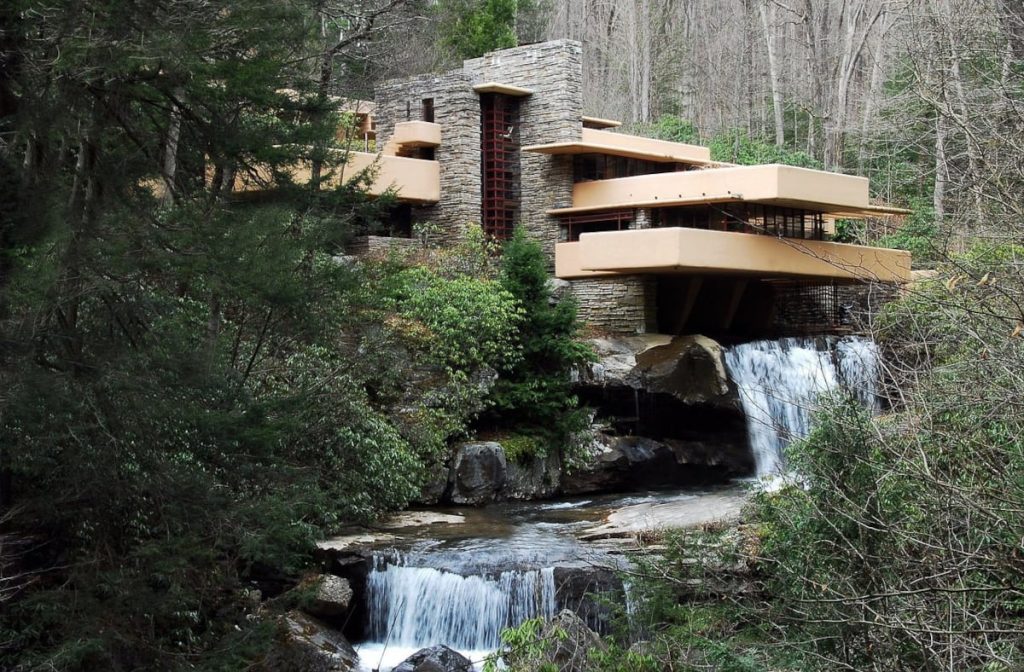

Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright

Location: Pennsylvania, USA

Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright

Completed: 1939

One of Wright’s most admired works, Fallingwater is a private residence situated dramatically over a waterfall. The cantilevered terraces and use of local materials gives the building a natural, organic feel seamlessly integrated with the site.

Sydney Opera House by Jørn Utzon

Location: Sydney, Australia

Architect: Jørn Utzon

Completed: 1973

The iconic seashell-esque vaulted roofs reference organic forms found in nature. Perched on the harbor, the Opera House feels symbiotically tied to its maritime site.

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao by Frank Gehry

Location: Bilbao, Spain

Architect: Frank Gehry

Completed: 1997

Frank Gehry’s landmark Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is a striking example of organic freeform architecture. Its curved, fragmented titanium forms are highly sculptural yet feel surprisingly organic and natural.

While controversial at the time, the museum’s fluid futuristic forms connected powerfully with the post-industrial cityscape along Bilbao’s Nervion River.

In designing the museum, Gehry took inspiration from the reflections and movement of the surrounding water. The resulting building feels rooted in its site through careful consideration of context, local climate, and materials despite its avant-garde forms.

Over 20 years since opening, Gehry’s design put Bilbao on the architectural map and remains an influential organic building.

Benefits

Sustainability

By integrating architecture into the natural environment, organic buildings conserve resources and reduce environmental impact. Strategies like passive heating, cooling, and lighting lower energy usage.

Biophilic Design

Nature-inspired architecture connects occupants to nature through design. This biophilic approach enhances wellbeing by fulfilling innate human desires to be close to nature.

Unique Sense of Place

Organic buildings feel intrinsically tied to location and climate, offering a strong sense of place. They resonate as being “of” a place rather than just “in” it.

Human-Scaled Design

Uses natural shapes and proportions comfortable to inhabit. Wright described organic buildings as “human-scale architecture.”

Integration of Spaces

Spaces connect and flow into one another. This openness encourages natural circulation and creates a unified whole.

Timelessness

By avoiding fleeting stylistic trends, the best organic architecture has a resonance and timeless quality.

Promotes Sustainability

Organic architecture aligns elegantly with the pillars of ecological and sustainable design. Here’s how it promotes sustainability:

Passive Design Strategies

Organic buildings leverage passive heating, cooling, ventilation, and lighting strategies. This reduces reliance on energy-intensive mechanical systems.

Renewable Materials

Utilizes natural and renewable building materials like wood, earth, and stone. Avoiding energy-intensive industrial materials decreases embodied energy.

Site Responsiveness

Buildings sited and oriented for optimal solar, ventilation, and drainage performance minimize resource use.

Smaller Footprints

Emphasizing quality over quantity encourages smaller footprints. Less building volume requires fewer materials.

Biophilic Connection

Satisfying our innate need to connect with nature promotes wellbeing. This reduces consumption driven by compensating for disconnection from nature.

Adaptability

Spaces designed with flexibility and flow can accommodate changing uses over time. This extends the building’s lifespan and reduces waste.

Challenges

While promising, executing organic architecture well presents challenges:

Higher Upfront Costs

Careful site-specific design and high-quality natural materials often increase upfront costs. However, this pays off long-term via lower operating costs.

Experimental Building

Pushing the boundaries of site-symbiotic architecture requires an experimental mindset. There are no set formulas or kits of parts.

Stringent Site Requirements

The approach relies on buildings growing from a particular site’s features. This limits site selection and orientation options.

Difficult Structures

Creating unconventional forms like cantilevers or thin shells requires greater structural and construction skills.

Maintenance

Using extensive natural materials and unconventional forms can increase maintenance requirements if not detailed properly.

Conclusion

While challenging to execute well, its emphasis on site-specific solutions, natural materials, and human-centric design offers many advantages.

At its best, organic architecture transcends stylistic trends and creates resilient, nourishing places tied intrinsically to landscape and community. This people-and-planet centered approach will only become more critical as we build a more sustainable future.

Related posts: